A Moment That Could Redefine India’s Future

Picture this: January 2026. Davos buzzes with global economic titans while India’s delegation enters not as spectator but as gamechanger reshaping global trade dynamics. On January 27th, India and the European Union signed what officials call the “The Mother of All Trade Deals” – a comprehensive strategic partnership that fundamentally transforms India’s relationship with the world’s largest economic bloc. The India-EU Tech Pact isn’t merely another trade agreement; it’s a historical inflection point that will ripple through India’s economy, society, and future trajectory for decades to come.

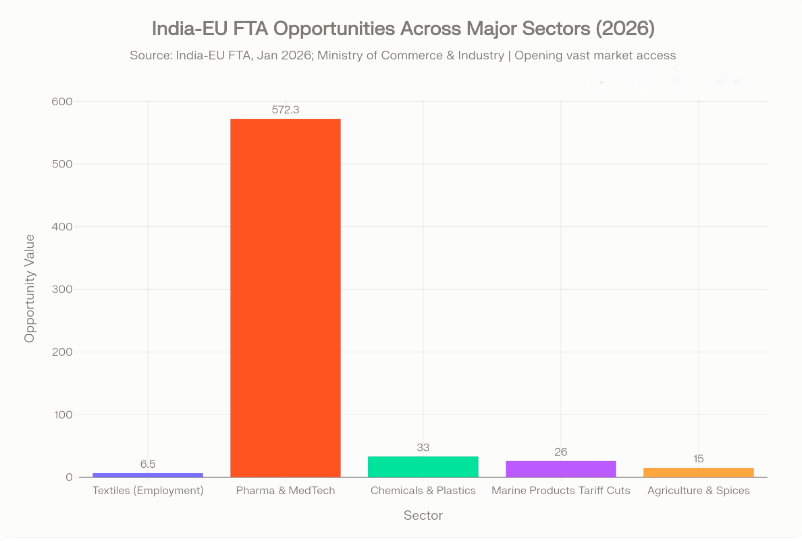

Here’s what happened in the snow-capped Swiss mountains: India gained zero-duty access to the €572.3 billion EU pharmaceutical market, unlocking unprecedented opportunities for our generic medicine manufacturers. Simultaneously, 6-7 million new jobs are projected in textiles alone – a sector employing 45 million Indians, predominantly women. Yet, beneath this celebratory narrative lies a deeper, more troubling question that few ask: Will these benefits actually reach India’s poorest citizens, or will they concentrate wealth among already privileged elites, deepening structural inequalities? That’s the story this analysis explores – unflinchingly and thoroughly.

Union Minister for Railways, Information & Broadcasting and Electronics & Information Technology, Ashwini Vaishnav declared at Davos 2026 that “India is no longer a consumer of technology but a co-creator,” signaling India’s arrival as a technology powerhouse capable of partnering with the world’s most advanced economies on equal terms. Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman emphasized that this agreement represents “Free Trade for Ambitious India, Free Trade for Aspirational Youth, and Free Trade for Aatmanirbhar India” – a self-reliant and confident India. Prime Minister Narendra Modi called India “a ray of hope for the world today,” positioning India as a stabilizing force amid global uncertainty. However, these powerful statements mask a critical challenge: ensuring the India-EU Tech Pact actually translates into tangible benefits for India’s informal workers, marginalized communities, struggling farmers, and 500 million citizens existing outside the formal economy.

The stakes couldn’t be higher. India’s trajectory hinges not merely on GDP growth rates, but on inclusive participation – ensuring prosperity reaches everywhere, not just to urban centers. This comprehensive analysis examines what the Davos Summit 2026 and India-EU Tech Pact actually mean for India across critical dimensions: technology leadership, digital inclusion, market access, labour migration, environmental justice, agricultural transformation, and inclusive growth pathways.

Technology leadership and semiconductor dominance

India’s AI ascendancy and chip design revolution

India’s positioning as a global technology powerhouse represents far more than hype – it is executable reality backed by concrete achievements. At Davos 2026, Ashwini Vaishnav revealed that 24 Indian startups currently design advanced 2-nanometer semiconductor chips, technology historically monopolized by the US, China, and South Korea for decades. Moreover, four semiconductor fabrication plants will commence commercial production during 2026 alone, fundamentally shifting global chip manufacturing geopolitics. India’s AI readiness ranks third globally in preparedness and second in pure talent density, positioning India alongside Silicon Valley and Beijing as a genuine innovation powerhouse. This isn’t aspirational positioning; it’s execution-driven reality built on years of investment, talent development, and strategic foresight.

The India-EU Tech Pact opportunities now extend this semiconductor leadership through unprecedented joint 6G research initiatives, secure semiconductor partnerships emphasizing quantum-resistant cryptography, and collaborative AI development focused explicitly on solving agricultural, healthcare, and climate challenges specific to developing economies. The EU Commission President, Ursula von der Leyen declared that “The deal brings together Indian skills, services and scale with Europe’s technology, capital and innovation,” signaling a fundamental shift from competitive zero-sum dynamics toward collaborative value creation. Furthermore, the India AI Impact Summit – scheduled for February 19-20, 2026, in New Delhi – will globally showcase India’s AI ecosystem, attracting technology leaders, policymakers, and investors from every continent. This represents India’s assertion of technological sovereignty and intellectual authority in shaping global AI governance standards.

6G and Quantum computing partnerships

The India-EU partnership commits to secure 6G development emphasizing citizen privacy, data localization, and national cybersecurity interests – departing fundamentally from previous Western-dominated telecommunications standards that often marginalized developing nations’ concerns. This cooperative framework acknowledges that technology standards shape power, and India deserves its space in designing infrastructure affecting 1.4 billion citizens. Joint 6G research centers will facilitate knowledge exchange, talent mobility, and intellectual property sharing through frameworks respecting both parties’ interests. Simultaneously, quantum computing partnerships create opportunities for Indian scientists and engineers to develop quantum applications addressing India-specific challenges: financial inclusion algorithms, agricultural optimization, climate modeling for Indian monsoon patterns, and epidemiological systems for disease surveillance. These aren’t theoretical collaborations – they represent India’s assertion that technology must serve local realities, not abstract global standards divorced from ground-level needs.

Additionally, innovation hubs dedicated to advanced semiconductors will establish research centers in Bangalore, Hyderabad, and Pune. Consequently, it will create thousands of high-wage technology jobs while building indigenous chip design capabilities that will reduce India’s dependence on foreign technology monopolies. When 6G infrastructure eventually deploys across India, this partnership will ensure that India’s tech might shapes its architecture, security protocols, and privacy frameworks. Nevertheless, critical questions persist: Will these innovation hubs deliberately recruit engineers from economically weaker sections, backward classes and female scientists, or will they inadvertently reproduce the elite – capture dynamics that exclude marginalized groups from technology’s highest-wage opportunities?

The digital divide crisis – Caste, Gender, and Exclusion

Caste-based digital exclusion and technology access

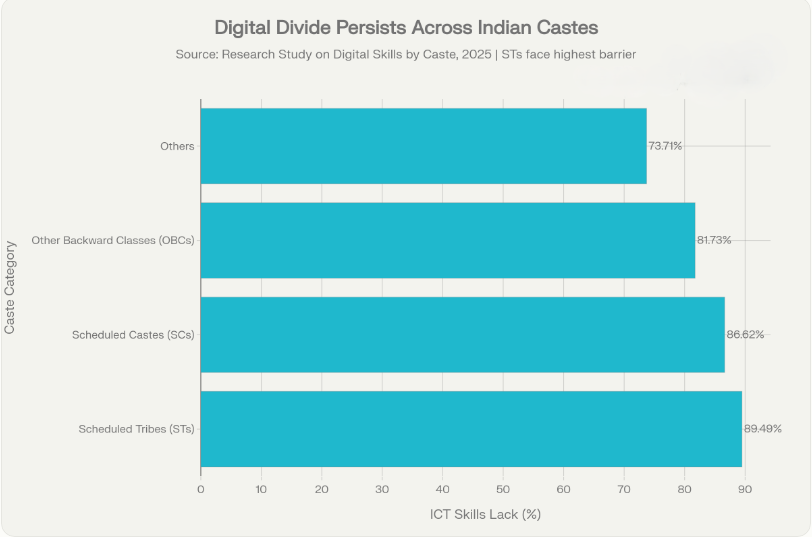

Here’s something India’s tech celebrants rarely mention: 89.49% of Scheduled Tribes and 86.62% of Scheduled Castes lack even basic Information and Communication Technology (ICT) skills – a structural exclusion so profound it demands immediate, and focused intervention. Besides, women comprise merely 13.91% of individuals possessing digital competencies nationally, compared to 22.78% of men, reflecting both occupational segregation and cultural barriers preventing women’s technology access. In Uttar Pradesh specifically, disparity widens further: only 6.93% of women versus 14.62% of men demonstrate digital skills, revealing how patriarchy intersects with technology exclusion. This isn’t merely statistical disparity; it represents systemic denial of economic opportunity, participation in digital governance, and voice in technology development – the very opportunities the India-EU Tech Pact supposedly unlocks.

Digital Divide in India by Caste (2025)

Source: Research Study on Digital Skills by Caste, 2025

Consider this paradox: India markets its Digital Public Infrastructure – Aadhaar, UPI, DigiLocker – as an inclusive global model worthy of adoption throughout the Global South, celebrating at Davos 2026 how these systems reached 1.4 billion citizens with financial services, government benefits, and digital identity. Nevertheless, Aadhaar’s very design mandates identity verification for welfare access, deliberately excluding landless Dalits without property documentation, undocumented migrants, and transgender citizens from essential services. Professor Nagendra Maurya, conducting research on digital equity, notes “You cannot separate the digital gap from the caste gap” – a statement encapsulating how technology exclusion perpetuates centuries-old caste hierarchies in digital form. When the India-EU Tech Pact opportunities roll out innovation hubs, semiconductor manufacturing, and 6G infrastructure, without intentional, binding mandates ensuring backward castes, women and economically weaker sections’ representation, these opportunities will concentrate only among upper-caste urban professionals, deepening structural inequality rather than addressing it.

Gender disparity in technology sectors and women’s participation

Women comprise 32% of India’s technology workforce – a figure stalled at near-parity with EU tech sectors at 32.8%, suggesting that neither India nor Europe has fundamentally solved gender exclusion in technology despite decades of diversity initiatives. The textile sector, primary beneficiary of India-EU FTA market access generating 6-7 million projected jobs, employs disproportionately high proportions of women – but simultaneously features the sector’s lowest wages, highest child labour risks, and severe working condition violations. Furthermore, the textile industry’s supply chains remain infamously opaque, with brand accountability mechanisms failing repeatedly to prevent exploitation of the predominantly female workforce producing garments for global consumption. The FTA’s binding International Labour Organization (ILO) core principles – freedom of association, collective bargaining rights, child labour elimination – are unprecedented in India’s trade agreements. However, enforcement mechanisms remain undefined, inspections lack teeth, and supply chain transparency faces corporate resistance.

Therefore, for the India-EU Tech Pact opportunities to authentically advance women’s empowerment, explicit mechanisms must mandate: gender quotas in innovation hub founder grants and mentorship programs; mandatory parental leave policies for both men and women; childcare support for women professionals accessing professional mobility benefits; zero-tolerance sexual harassment enforcement in tech workplaces; and transparent reporting on gender wage gaps across firms benefiting from tariff reductions. Additionally, women entrepreneurs must gain preferential access to EU-India Startup Partnership funding, ensuring female founders capture proportionate share of investment capital flowing through these channels. Without such deliberate, enforced mandates, women will remain tokenized in technology’s upper echelons while remaining overrepresented in precarious, low-wage service sectors.

Market access revolution – Textiles, Pharma, and Sectoral opportunities

Six to seven million textile jobs – but at what cost?

The numbers initially appear staggering enough to celebrate: the India-EU Trade Deal is projected to create 6-7 million new employment opportunities in textiles alone, a sector currently employing 45 million people, making it India’s second-largest employment provider after agriculture. This means expanded factories, new production units, increased demand for skilled workers, and theoretically rising wages reflecting productivity improvements and global competitiveness gains. However, beneath these optimistic projections lurk uncomfortable realities rarely discussed in policy circles or celebratory media coverage. Textile sector workers earn among India’s lowest wage – approximately ₹8,000-12,000 monthly for field workers and ₹12,000-18,000 for factory workers – well below living wage calculations that account for food, housing, healthcare, and education costs. Additionally, 80% of textile workers are women, yet they comprise less than 5% of management and supervisory positions, reflecting how patriarchal structures exploit female labour while reserving control for men.

India-EU FTA Sector-wise Opportunities (2026)

Source: India-EU FTA, Jan 2026, Ministry of Commerce & Industry

Consider a related concern: Will expanded textile production for EU markets incentivize automation to reduce labour costs, ultimately eliminating jobs rather than expanding them? European firms increasingly demand compliance with strict labour standards, environmental sustainability requirements, and wage transparency – all positive developments. However, these demands simultaneously pressure Indian manufacturers to mechanize production, replacing human workers with robots, thereby potentially reducing rather than expanding employment despite market access expansion. The FTA’s binding ILO commitments represent genuine progress, yet enforcement relies on supplier self-reporting, third-party audits vulnerable to corruption, and trade unions accessing supply chains – an ideal scenario rarely realized in contemporary global manufacturing. Therefore, 6-7 million new textile jobs might represent aspirational maximum rather than realistic baseline, with actual job creation dependent entirely on implementation quality, enforcement rigour, and union presence throughout supply chains.

Pharmaceutical and medical device market access

India gains unprecedented zero-duty access to the European Union’s €572.3 billion pharmaceutical and medical technology market, potentially generating $5.8 billion in additional annual pharmaceutical exports while opening medical device opportunities worth billions. India, recognized globally as the “pharmacy of the developing world,” manufactures 50% of global vaccine doses, 20% of global generic medicines, and supplies affordable medications to over 140 countries throughout Africa, Asia, and Latin America. This EU market access amplifies India’s capacity to serve European citizens seeking affordable alternatives to expensive brand-name pharmaceuticals, positioning India as an essential partner in European healthcare systems confronting escalating medication costs which threaten fiscal sustainability.

Some tough questions demand attention: Will Indian pharmaceutical workers enjoy safer conditions, higher wages, and stronger labour protections from this boom, or will corporations capture all gains while labour remains vulnerable to exploitation? Indian pharmaceutical manufacturing workers face exposure to hazardous chemicals, inadequate safety equipment, and employer resistance to collective bargaining arrangements. The FTA’s labour standards chapters are binding, yet pharmaceutical companies historically resist union organization, exploit contract labour to circumvent regulations, and lobby against worker-protective amendments. Additionally, the Generic Medicines Council fears that strict intellectual property enforcement might increase barriers to generic medicine production, potentially compromising India’s ability to manufacture affordable medicines for its own population. Therefore, the €572.3 billion market opportunity means little if Indian workers remain exploited while corporations extract massive profits.

Labour migration and professional mobility – Opportunities and Risks

Unprecedented professional mobility framework

The FTA’s professional mobility framework represents genuinely extraordinary opportunities, unprecedented in India’s trade relationship history. The agreement opens 144 services subsectors for Indian business professionals, IT specialists, contractual service suppliers, and independent professionals seeking temporary work in EU member states. Post-study work visas extend to Indian students graduating from EU universities, enabling them to gain European work experience before potentially returning to India with international skills and networks. Social Security Agreements prevent double contributions, ensuring Indian professionals abroad accumulate pension benefits rather than losing contributions when relocating. This framework potentially mobilizes India’s demographic dividend – 700 million under-30 population – toward higher-wage employment internationally, generating remittances supporting families while building human capital through international exposure.

However, specific risks warrant careful consideration: Will Indian professionals in EU firms encounter wage discrimination based on nationality or skin colour? Historical evidence from visa sponsorship systems reveals systematic wage gaps between Western professionals and South Asian professionals performing identical roles. Additionally, visa-tied status makes Indian workers vulnerable to employer exploitation – threats of visa cancellation pressure workers to accept substandard conditions, wage theft, and workplace abuse. The framework emphasizes “talent extraction” language, potentially benefiting EU employers seeking cost-efficient professionals while India loses skilled workers needed domestically. While Davos 2026 celebrates India becoming the world’s third-largest economy, India simultaneously exports precisely the engineers, doctors, and talented professionals necessary for achieving domestic development aspirations. Therefore, while professional mobility represents genuine opportunity for individual advancement, national policy must simultaneously invest in reversing brain drain through competitive domestic wages, research funding, and innovation ecosystems preventing systematic talent loss.

The informal economy’s exclusion from mobility benefits

The professional mobility framework serves exclusively formal, credentialed professionals – engineers, lawyers, consultants, IT specialists – while systematically excluding the 500 million informal workers comprising 45% of India’s GDP. Street vendors, domestic workers, agricultural labourers, informal traders, and gig workers receive no mobility benefits despite their contributions to economic activity. This selective inclusion deepens inequality: formal sector professionals enjoy EU work rights, competitive wages, and social protections, while informal workers watch opportunities pass them by, facing intensifying competition from digital platforms replacing traditional commerce. Moreover, EU expansion might incentivize Indian firms to mechanize and formalize operations, directly threatening informal worker livelihoods without providing transition support or alternative income sources. The FTA’s silence on informal economy integration represents a critical policy gap demanding urgent attention through complementary domestic initiatives.

Green energy and Climate justice – Opportunities and Displacement risks

€712 billion investment in clean energy – Who benefits?

The India-EU Clean Energy and Climate Partnership Phase 3 allocates €712 billion toward renewable energy projects, green hydrogen development, and offshore wind infrastructure – the largest climate finance commitment in India-EU relationship history. This investment ostensibly accelerates India’s Net Zero 2047 commitment, transitions energy systems away from coal dependence, and positions India as a clean energy manufacturing superpower capable of exporting solar panels, wind turbines, and battery technology globally. The partnership acknowledges India’s “Common But Differentiated Responsibilities” principle – recognizing that developed nations industrialized through carbon-intensive manufacturing, so developing economies deserve space for growth while transitioning toward sustainability.

Nevertheless, green energy projects historically displace rural and tribal communities through land acquisition, dam construction, and infrastructure development without adequate consent or compensation mechanisms. India’s 270 million climate-vulnerable citizens – living in flood-prone river deltas, drought-stricken regions, and cyclone-exposed coastal areas – face “just transition” risks where green infrastructure projects sacrifice their livelihoods for global climate goals. Solar farms consume vast agricultural land, potentially reducing food production and undermining farmer welfare. Hydroelectric dams flood tribal territories, destroying indigenous cultures and knowledge systems. Green hydrogen projects require massive water consumption in already water-stressed regions. Therefore, €712 billion investment means little if it concentrates wealth among corporations while displacing millions from ancestral lands.

Environmental justice and community-centered climate solutions

Authentic climate justice demands that green energy projects implement Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) frameworks giving affected communities absolute right to approve or reject projects affecting their territories. This means indigenous land rights become non-negotiable, climate finance reaches poorest regions through community-controlled mechanisms rather than top-down corporate projects, and environmental impact assessments center affected communities’ voices rather than merely consulting them performatively. Additionally, green job training programs must explicitly reach backward-caste communities, women, and informal workers, ensuring that clean energy transitions create inclusive prosperity rather than perpetuating just the elite.

Agricultural transformation – Market access and Farmer welfare

Zero-duty access for processed foods – Benefits and Concerns

The India-EU FTA provides zero-duty market access for processed agricultural products – tea, coffee, spices, table grapes, gherkins, processed foods – enabling Indian agro-processors to access the EU market at unprecedented cost advantages. This seemingly benefits agricultural value addition, enabling farmers to sell processed products commanding higher prices than raw commodities. India’s tea exports gain preferential access to EU markets valuing Assam and Darjeeling tea globally; coffee farmers access premium European markets; spice producers can expand significantly. Simultaneously, the agreement strategically protects sensitive sectors – dairy, cereals (rice), poultry, soymeal, select fruits and vegetables – ensuring small and marginal farmers receive safeguards against European competition that might devastate India’s 900+ million farming population.

However, concerns persist: Will benefits concentrate among agribusiness corporations and large-scale agricultural processors, or will small farmers actually access these opportunities? India’s agriculture remains dominated by 86% marginal and small landholders lacking resources, technology, and market access necessary for profitable production. Therefore, tariff reductions benefit them only if complementary policies enable market participation – rural credit systems, agricultural inputs availability, storage infrastructure, processing facilities, and buyer networks connecting farmers to EU markets. Without such complementary initiatives, large agribusinesses will capture all gains while small farmers face increased competition from imported products, potentially accelerating agricultural distress and farmer suicides prevalent in export-oriented agricultural regions.

Protected sectors and Food security implications

Strategic protection of dairy, cereals, and poultry sectors reflects recognition that farming remains the survival livelihood for hundreds of millions of Indians dependent on agricultural income. Dairy protection safeguards millions of rural women earning income through milk production; rice protection ensures food security for India’s staple grain-dependent population; poultry protection supports small-scale farmers in southern and eastern India. These protections represent genuine policy victory ensuring that trade liberalization doesn’t devastate vulnerable farming communities. Nevertheless, ongoing farm distress – farmer suicides, agricultural indebtedness, youth migration from villages – suggests that tariff protection alone proves insufficient without parallel investments in agricultural productivity, crop insurance, market infrastructure, and viable livelihood alternatives for generations exiting farming.

Data privacy and Digital sovereignty

GDPR vs. DPDP – Whose values shape Digital governance?

India’s Digital Personal Data Protection Act (DPDP) diverges fundamentally from the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) on critical governance questions. GDPR emphasizes citizen consent, strict data minimization, and individual rights to access, correction, and deletion – fundamentally empowering citizens relative to governments and corporations. Conversely, DPDP grants Indian government broad latitude to access citizen data under “national security” and “public order” justifications, creating pathways for state surveillance potentially targeting political opponents, religious minorities, and social activists. As India and the EU harmonize digital governance standards through the India-EU Tech Pact, whose values will prevail – citizen-centric privacy emphasis or government-centric security emphasis?

This divergence becomes critical when considering 6G infrastructure development and Artificial intelligence applications. If 6G networks and AI systems get designed under surveillance-enabling standards, marginalized communities face intensified monitoring risk. Dalit activists, religious minorities, labour organizers, and political opponents already face systematic state surveillance throughout South Asia; 6G infrastructure with weak privacy protections would exponentially amplify this surveillance capacity, enabling mass monitoring devastating to democratic freedom and human rights.

Data localization and Surveillance architecture

India’s data localization requirements mandate that certain data categories – “critical” data affecting national security, financial systems, and government operations – remain physically stored within Indian territory rather than cloud infrastructure controlled by US or Chinese corporations. This represents genuine digital sovereignty assertion, preventing foreign governments from accessing Indian citizen data through corporate surveillance partnerships. Nevertheless, data localization requirements simultaneously enable Indian state surveillance by creating domestic infrastructure where government can access citizen data with minimal foreign oversight.

Therefore, authentic digital security demands binding privacy safeguards protecting citizens from both foreign corporate surveillance and domestic government overreach. India-EU partnerships must establish clear rules preventing surveillance of marginalized communities, mandate transparent algorithms preventing discriminatory AI decision-making affecting vulnerable populations, and establish independent oversight mechanisms monitoring surveillance systems rather than merely trusting government self-restraint.

Informal sector and Digital transformation

The 500 million workers invisible in trade negotiations

Here’s what trade policy discussions consistently omit: 45% of India’s gross domestic product originates from the informal economy – street vendors, domestic workers, agricultural labourers, unregistered small enterprises, gig workers – yet these 500 million workers receive negligible attention in FTA negotiations, policy design, and implementation planning. When India-EU Tech Pact opportunities emphasize formal services – IT professionals, pharmaceutical companies, organized textile manufacturers – informal workers watch from the margins knowing that trade liberalization will intensify competition, potentially destroying their livelihoods without providing alternatives or transition support. Digital platform expansion – Amazon, Flipkart, Uber, Swiggy etc – eliminates street vendor livelihoods while offering gig work featuring low pay, zero protections, and algorithmic management enabling systematic exploitation.

The FTA’s Social Security Agreements cover only formal workers enjoying registered employment status. When e-commerce platforms scale, when digital payments systems expand, when gig economy multiplies, informal workers get systematically excluded from labour protections, pension benefits, and social security coverage that formal workers enjoy. This represents a critical policy failure demanding urgent attention: informal economy integration into digital infrastructure must include explicit protections – portable benefits, gig worker insurance, microcredit access, and digital payment systems lowering transaction costs for vulnerable populations.

E-Shram integration and Digital financial inclusion

India’s e-Shram platform – registering 300+ million informal workers digitally – creates unprecedented opportunity to extend protections, benefits, and credit access to workers historically excluded from formal systems. Nevertheless, e-Shram integration into digital public infrastructure requires parallel policy reforms: guaranteed minimum income schemes supporting informal workers during transitions; subsidized digital payment systems eliminating transaction cost barriers; cooperative ownership models enabling informal workers to collectively own platforms rather than merely working for corporations; and regulatory frameworks preventing algorithmic discrimination affecting vulnerable workers. Without such complementary policies, digital transformation will deepen informal worker marginalization rather than enabling genuine inclusion.

Holistic changes required for inclusive growth

Policy reforms and institutional capacity building

For the India-EU Tech Pact opportunities to deliver genuine inclusive growth benefiting all Indians – not just privileged elites – urgent policy interventions must occur:

First, establish binding caste-conscious digital inclusion mandates. Innovation hubs must reserve founder grants, mentorship positions, and equity allocations for Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe entrepreneurs. Digital literacy programs must target marginalized communities explicitly. Universities must reserve technology field admissions for backward-caste students. Infrastructure rollout – 5G, 6G, broadband – must prioritize underserved regions and marginalized communities rather than profitable urban markets. These aren’t suggestions; they represent policy imperatives for ethical technology deployment.

Second, strengthen labour rights enforcement across entire supply chains. Trade unions must gain access to supply chain facilities for independent verification of working conditions. Third-party audits must replace self-reporting systems enabling corporate deception. Wage councils must ensure workers share productivity gains rather than capturing profits exclusively for shareholders. Sectoral minimum wages must adjust for inflation and living costs, ensuring workers earn dignified incomes. Child labour must face zero tolerance with enforcement resources matching severity of violations.

Third, mandate aggressive gender equity targets in technology sectors. Women comprise 13.91% of those with digital skills – a figure demanding urgent intervention through reserved seats in tech training programs, preferential hiring targets for women in technology companies, childcare support enabling women professionals’ participation, and zero-tolerance sexual harassment enforcement with meaningful penalties. Gender wage audit transparency must require firms benefiting from tariff reductions to publicly report gender pay gaps, enabling accountability and corrective action.

Fourth, extend digital infrastructure access to informal workers. Gig workers, domestic workers, street traders, and agricultural labourers must gain access to digital systems without identity requirements excluding landless citizens. E-Shram integration must provide portable benefits, microcredit access, and pension coverage. Digital payment systems must subsidize transaction costs for poorest populations, ensuring that financial inclusion benefits reach those most vulnerable to exploitation.

Fifth, ensure genuine environmental justice in climate projects. Free, Prior, and Informed Consent frameworks must give affected communities absolute authority over projects affecting their territories. Indigenous land rights must become non-negotiable foundations for climate action. Community-controlled climate finance mechanisms must ensure that benefits reach the poorest regions. Green job training must explicitly target backward castes, women, and informal workers, creating inclusive clean energy transitions.

Social mobilization and Civic engagement

Beyond policy reforms, authentic inclusive growth requires active citizen participation demanding accountability. Civil society organizations must monitor FTA implementation, investigate supply chain violations, document worker exploitation, and publicize corporate malfeasance deterring bad actors while rewarding ethical firms. Labour unions must organize textile workers, pharmaceutical workers, and informal workers into collective bargaining units capable of negotiating dignified conditions. Community organizations must defend farmer interests against agricultural distress while advocating for small farmer support systems. Women’s groups must demand gender equity implementation through public campaigns, shareholder activism, and regulatory pressure on technology companies. Dalit organizations must demand caste equity mandates in technology sectors, preventing perpetuation of caste hierarchies in digital forms.

Furthermore, individual citizens must engage in informed civic participation: reading FTA clauses, asking questions about labour conditions in products purchased, participating in community discussions about infrastructure development, and refusing exploitation of marginalized workers through purchasing choices. Democracy demands engagement; prosperity requires solidarity across divides – refusing to celebrate gains concentrated among elites while communities remain vulnerable.

Personal development and Skill building for inclusive futures

Upskilling and deliberate equity in technology access

The India-EU Tech Pact opportunities create genuine pathways for personal advancement through technology skills acquisition, international work experience, and access to global innovation ecosystems. However, benefiting from these opportunities requires deliberate choice to build skills while maintaining commitment to equity. This means pursuing technology education while mentoring backward-caste and female peers entering fields historically excluding them. It means entering technology professions while advocating within firms for caste-conscious hiring, gender equity, and wage justice. It means building personal success while refusing complicity with exploitation – withdrawing labour and pressure from firms engaging in supply chain violations, unsafe practices, or worker exploitation.

Furthermore, skill development must extend beyond elite technical fields toward intermediate occupations serving informal economies: digital literacy for street vendors, e-commerce platform training enabling informal traders to reach customers, financial literacy supporting informal workers’ credit access, and cooperative formation skills enabling collective ownership. India’s success depends not merely on AI researchers and chip designers – important though they are – but on 500 million informal workers gaining digital competencies enabling their participation in expanding the digital economy.

Building solidarity across economic divides

Technology’s benefits concentrate unless citizens actively push for equity through solidarity, collective action, and refusing to accept inequality as inevitable. Upper-caste urban professionals must leverage their privilege – easier access to elite educational institutions, professional networks, social capital – to deliberately create pathways enabling Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe professionals’ advancement, refusing gatekeeping practices perpetuating exclusion. Male technologists must actively amplify women’s voices in technology spaces, refuse to dominate discussions, and mentor female professionals into leadership. Formal workers must stand in solidarity with informal workers, supporting unions, collective bargaining agreements, and minimum wage standards protecting vulnerable populations from exploitation. Wealthy Indians must support policies redistributing wealth toward marginalized communities rather than resisting taxation and social protections. Privileged segments must recognize that inclusive growth serves everyone – stable economies, reduced conflict, and sustainable societies benefit all citizens regardless of current wealth.

Seizing the moment or reproducing inequality?

The Davos Summit and the India-EU Tech Pact represent genuinely historic inflection points reshaping India’s global position, economic trajectory, and technological future. India stands poised to capture €572.3 billion pharmaceutical markets, deploy world-leading 6G technology, create millions of jobs across textiles and services, attract foreign investment, strengthen manufacturing competitiveness, and position itself as a trusted leader of the Global South – all genuine opportunities worthy of celebration. The partnership represents India’s assertion of technological sovereignty, intellectual authority, and strategic autonomy in shaping global standards rather than merely consuming Western-designed systems.

However, the India-EU Tech Pact opportunities mean devastatingly little if they concentrate wealth among already privileged elites – urban professionals, large corporations, established firms – while deepening inequality for marginalized communities, informal workers, and struggling farmers. The caste-digital divide could widen; women could remain underrepresented in technology’s highest-wage opportunities; informal workers could face livelihood destruction; rural communities could lose agricultural livelihoods and land to green infrastructure projects; and supply chain workers could endure continued exploitation despite binding ILO commitments. India possesses genuine choice: Will technology serve all Indians equitably, or merely reinforce existing hierarchies in digital form? Will Davos Summit 2026 rhetoric about inclusive growth translate into binding commitments, enforcement mechanisms, and institutional capacity genuinely benefiting India’s poorest citizens?

The answer depends not on government policy alone, but on each of us – demanding accountability from corporations and policymakers, building equity through deliberate choice and solidarity, mentoring marginalized peers into opportunities, supporting collective action defending vulnerable workers, and refusing to celebrate growth concentrated among elites. India’s future hangs in the balance. The choice is ours – and the moment demands nothing less than our most committed, ethical engagement in ensuring that prosperity reaches everywhere and everyone in India.

The moment is now. India’s inclusive future depends on your choices and voices. Make it matter!! 🗣️🎤📢

#IndiaEUTradeDeal #Davos2026 #IndiaTech #DigitalIndia #FTA2026

Davos deal is not a big thing to celebrate.

Signing many MOUs for FDI is not any achievement.

Many MOUs are projected for ten, twenty, thirty years. By that time there is no guarantee that the FDI will actually reach India.

India still has 80 crore people receiving fee ration. That means the poverty index is 103 out of 143 countries.

What is needed is to find out indigenous technologies and technicians to employ local citizens to make world standard goods, export them and earn foreign exchange and lift the living standards of our citizens.

Let us create many wealth creators; not just two.

Claiming Indo-UK agreement or being vishvaguru does not solve our problems.

First let us set our house in order.